(in Percentage)By Vikas Meena and Anuradha Barua

Water has always been more than a resource, it has been the framework of survival, shaping economies, building cultures, and defining the rhythms of daily life. In India, where landscapes shift from arid deserts to floodplains within a few hundred miles, water is the force that defines how people live, earn, and adapt. It is also the front where the impacts of climate change are most visible.

From the deserts of Rajasthan to the floodplains of Assam, India experiences both ends of the hydrological spectrum. These two states, though separated by geographies, tell us the same story: adaptation is not abstract—it is lived, local, and urgent.

Rajasthan and Assam: Contrasting Realities of Water

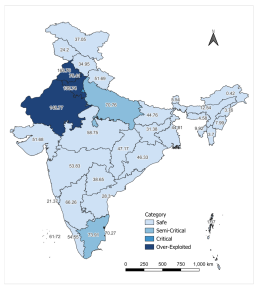

Rajasthan, India’s largest state, is also its most water-stressed. It receives less than 500 mm of annual rainfall, among the lowest in the country, compared with the national average of over 1,000 mm.[1] Rivers like the Luni and Sabarmati run only seasonally, and groundwater has long become the lifeline for its people. But that lifeline is under threat. Rajasthan is one of only three states in India where groundwater withdrawals exceed recharge, with an extraction rate exceeding 100%. Already 62% of its groundwater blocks are marked “critical” or “over-exploited”[2]. The wells are drying up, salinity is creeping into aquifers, and in some areas, land subsidence risks are increasing.

Stage of Groundwater Extraction, 2023 (in percentage)

Stage of Groundwater Extraction, 2023 (in percentage)

But Rajasthan’s story is not just about crisis, it is also of ingenuity. For centuries, its communities developed baoris (stepwells), johads (earthen check dams), nadis (ponds), and khadeens (temporary lakes) which allowed them to capture and conserve rainwater and recharge groundwater.

Chand Baori (Stepwell) in the Abhaneri, Rajasthan

Chand Baori (Stepwell) in the Abhaneri, Rajasthan

A Johad in Thathawata, Rajasthan

A Johad in Thathawata, Rajasthan

Agriculture adapted too, relying on hardy crops like millet, pulses, and oilseeds that demand less water. Today, modern interventions like drip and micro-irrigation, alongside the vast Indira Gandhi Canal, provide critical support. Rajasthan’s enduring message is clear: survival rests on restraint; using less, conserving what exists, and managing water as a collective responsibility.

In Assam, the story flips entirely. Here, rainfall exceeds 2,000 mm annually; more than four times Rajasthan’s average. Its fertile plains, nourished by the mighty Brahmaputra and its tributaries, make it one of India’s most agriculturally productive regions, and also one of its most volatile. Every monsoon, Assam experiences devastating floods. In 2024, floods swept through 2,800 villages, displacing hundreds of thousands of people and damaging crops and infrastructure. In severe years, nearly a fifth of the state’s population is affected.[3]

Floods in Assam are not occasional disasters; they are recurring realities. And so people have adapted through practices rooted in local wisdom. Homes rise on stilts, offering families safety when the waters rise. Farmers grow rice varieties that can withstand standing water, while fish farming not only becomes a source of food but also acts as an important safety net when crops are lost. The state government has strengthened flood forecasting and early-warning systems, and embankments now protect stretches of riverbank. But these measures cannot always hold back the force of the Brahmaputra. When the river breaks its banks, it is often locals and community groups in the frontline, ferrying stranded families, opening their homes as shelter, and helping villages rebuild their lives together after the waters recede.

Assam’s lesson is equally stark: resilience is not about eliminating risk. It is about living with it, adapting to it, and finding strength in collective response.

Sang Ghar (Stilted House), Assam

Sang Ghar (Stilted House), Assam

Flood Rescue in Kokrajhar, Assam

Two Extremes, One Climate Imperative

Seen together, Rajasthan and Assam reveal the two contrasting faces of India’s water paradox. Rajasthan shows the danger of leaning too heavily on a resource that is steadily running out. Its groundwater reserves are being drained more quickly than they can be replenished, putting farming and rural livelihoods at serious risk. Assam, meanwhile lives with the challenge of abundance. The same water that nourishes the land turns destructive during the monsoons. Climate change doesn’t simply exacerbate these problems—it reshapes them entirely.

In Rajasthan, blistering summers stretch on for longer, pushing water demand higher just when recharge opportunities shrink. Recent analysis suggests rainfall may dip by as much as 20% by 2050, leaving recharge, especially in places like Jaipur and Jodhpur, dangerously low with groundwater levels already in decline.[4] In Assam, the monsoon pattern has turned increasingly capricious. Rains are heavier, more intense, and often arrive with little warning, bringing floods that strike with greater force. At the same time, the season itself has grown unpredictable: arriving late, lingering or bursting early. This volatility is already eroding livelihoods. Even with episodes of extreme downpour in recent years, the state recorded a 14% deficit in pre-monsoon rainfall between March 1 and May 21, showing how even intermittent cloudbursts fail to balance out longer dry spells.[5] The result is a cycle of unpredictability in which delayed monsoons aggravate flooding, while erratic rainfall patterns impact farming calendars and disaster preparedness.

Together, these shifting patterns highlight a critical reality: there is no one-size-fits-all solution to adaptation. Rajasthan’s arid zones require water efficiency, aquifer recharge, and climate-smart cropping. Assam’s floodplains demand strategies that centre on resilience, diversified livelihoods, flood-aware infrastructure, and early warning systems to buffer communities from the unpredictable dangers of changing monsoons.

Water for Climate Action

As the world observes Water Week 2025, the theme “Water for Climate Action” finds clear expression in the experiences of Rajasthan and Assam. These two states show that water is both the first casualty of climate change and the first line of defence in adaptation. Rajasthan’s overdrawn aquifers and Assam’s unpredictable floods may appear as opposite challenges, yet they point to the same truth: effective climate action begins with how we manage the resource itself.

India’s geography underlines an urgent truth: sustainable water management is not just adaptation; it is the foundation of climate security. Protecting aquifers, restoring wetlands, improving flood preparedness, and investing in resilient infrastructure are urgent imperatives. Equally important is empowering local communities, the first responders and custodians of centuries of knowledge in adapting to scarcity or excess.

The stories of Rajasthan and Assam are more than regional stories, they hold lessons for all of us. One state survives by using less; the other survives by enduring more. Both require strong local institutions, investment in community capacity and policies grounded in ecological limits. But the lesson is broader: climate adaptation cannot be a distant plan or a line in a policy document. It requires choices, responsibility, and action today.

- https://phedwater.rajasthan.gov.in/

- https://cgwb.gov.in/cgwbpnm/public/uploads/documents/17357169591419696804file.pdf

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/natural-disasters/assam-floods-2024-unprecedented-timing-and-fury-grips-state

- https://www.woarjournals.org/admin/vol_issue1/upload%20Image/IJGAES111108.pdf

- https://assamtribune.com/opinion/from-predictable-to-perilous-how-climate-change-is-reshaping-the-monsoon-1578468