By Chandrani Chakraborty , PhD Research Scholar, Department of Legal Studies, Motherhood University, Roorkee

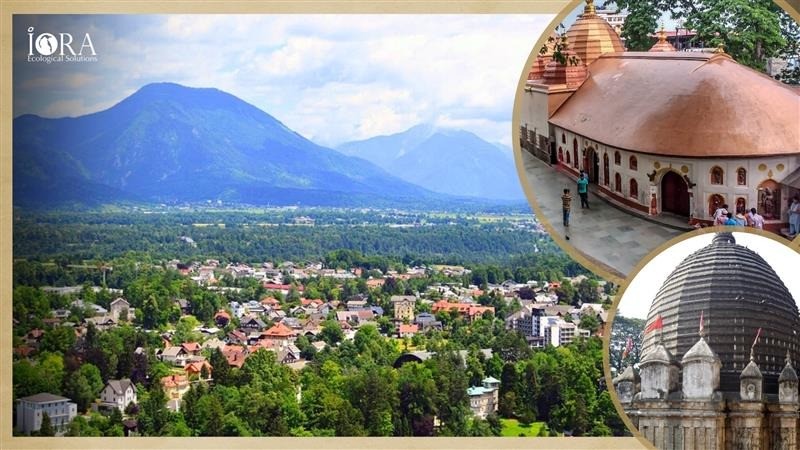

Situated atop Guwahati’s Nilachal Hills, the Kamakhya Temple is not just one of India’s most revered Shakti Peethas, but also a sacred ecological landscape. Dedicated to Goddess Kamakhya, it embodies centuries-old tantric traditions deeply intertwined with nature. This is where the divine feminine energy is worshipped in her most primal form: not through idols, but through a sacred yoni-shaped rock believed to symbolize the Shakti herself. Rituals are performed not just in the temples, but within sacred springs, groves, and indigenous flora.

However, today this fragile spiritual-ecological landscape stands at a crossroad.

The proposed Kamakhya Corridor Project, which aims to enhance infrastructure and pilgrim convenience, has sparked growing concerns over ecological damage, cultural disruption, and procedural lapses.

In Kamakhya, the act of worship is not merely about a visual darshan, but about immersion into a ritual ecosystem that includes tribal priests, tantric practitioners, and women-led religious practices. Streamlining such a sacred space into a tourism-centric corridor threatens to marginalize these actors and their practices. Additionally, there has been inadequate consultation with local stakeholders, including indigenous communities and traditional caretakers of the temple, raising concerns about cultural alienation.

The Nilachal Hills form part of the Eastern Himalayan foothills, is a biodiversity hotspot, home to unique flora and fauna, many of which are essential to the temple’s ritual practices. Its natural springs, in particular, are vital for temple ceremonies and also support local water needs. Recognising their importance, researchers at IIT Guwahati initiated a collaborative conservation project to map, study, and revive these ancient springs. The project acknowledges their hydrological, cultural, and ecological value and seeks to ensure their sustainability through scientific assessment and community engagement.

Yet, large-scale excavation and construction under the corridor plan could endanger these very sources, altering underground water flows and threatening their longevity.

The warning signs are already flashing. Environmental experts have raised alarms on unscientific hill-cutting, deforestation, and slope-flattening to accommodate roads, waiting areas, and concrete structures. These interventions risk triggering landslides, soil erosion, and severe depletion of groundwater. The loss of tree cover would disrupt microclimates, displace bird species, and affect the natural drainage systems that are essential to the monsoon-driven terrain. More critically, these interventions could jeopardize the delicate balance of the Nilachal ecosystem, especially the underground rivulets and sacred springs that not only sustain biodiversity but also hold spiritual significance for temple rituals and festivals like Ambubachi Mela.

From a legal standpoint, the Kamakhya Corridor has raised red flags for bypassing crucial environmental and procedural safeguards. In March 2024, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) issued notice to the Assam Government following a petition that alleged violations of environmental clearance norms. Under the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification (2006) any large-scale construction in ecologically sensitive zones requires prior Environmental Clearance (EC), which appears to have been neglected. Similarly, the Forest (Conservation) Act (1980) and the Biological Diversity Act, (2002) mandate that any intervention impacting forest land or biodiversity must involve consultation with local forest officials and biodiversity management committees. Reports suggest that these statutory requirements were not fulfilled.

Further, the project allegedly excluded key local governance institutions from the decision-making process, including Gram Sabhas and the Kamakhya Debutter Board, which traditionally manages the temple’s affairs. This violates principles of decentralised governance enshrined under the Panchayati Raj Act and undermines the right to local self-determination in matters concerning heritage and ecology. The lack of free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous communities contravenes the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, which empowers forest dwellers to protect and manage their traditional forest resources.

At the constitutional level, the Kamakhya Corridor case raises significant concerns. Article 48A of the Constitution, a Directive Principle of State Policy, directs the State to protect and improve the environment and safeguard forests and wildlife. Article 51A(g) imposes a fundamental duty on every citizen to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures. Disregard for these principles, especially in the name of religious development, reflects a growing dissonance between cultural preservation and environmental justice.

Kamakhya’s story is not unique. We have seen similar patterns in the Mahakal Lok Corridor in Ujjain and the Kashi Vishwanath Dham in Varanasi. Both were ambitious attempts to merge spirituality and infrastructure, but faced criticism for poor planning, environmental damage, and disregard for cultural nuance. The Mahakal project suffered structural damage within months of inauguration, while the Kashi corridor displaced numerous homes and heritage structures. These precedents suggest that faith-based infrastructure, if not rooted in local realities, risks becoming a spectacle devoid of soul.

Kamakhya offers a chance to break this pattern and learn from these activities. Instead of replicating flawed models, the focus must shift to ecologically mindful and culturally sensitive development. A thorough and transparent EIA process, guided by scientific institutions like IIT Guwahati and monitored by the judiciary, must precede any further activity. Stakeholder consultations must include all stakeholders–temple priests, indigenous communities, biodiversity experts, and local governing bodies. The idea of eco-pilgrimage—promoting spiritual journeys that protect rather than exploit the environment—can offer a sustainable alternative to concrete-heavy corridors.

To sum up, while the ambition to enhance pilgrim access and infrastructure around the Kamakhya Temple is understandable, it must not come at the cost of eroding the site’s unique spiritual identity and ecological harmony. The failures of the Mahakal and Kashi Vishwanath corridors remind us that sacred spaces are not blank slates for architectural imagination, but living repositories of collective memory, belief, and biodiversity.

Kamakhya deserves a development model that is rooted in respect, restraint, and reverence—not one that confuses sanctity with spectacle. We must ensure that Kamakhya remains a sanctuary of spiritual and ecological harmony, honoring its profound significance for generations to come.

Reference:

- Bhandari, M. (2023). Faith, development, and environmental governance in South Asia. Journal of Environmental Policy and Law, 53(2), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.3233/EPL-230045

- Gadgil, M., & Guha, R. (1995). Ecology and equity: The use and abuse of nature in contemporary India. Routledge.

- Government of India. (2006). Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Retrieved from https://moef.gov.in

- Leelakrishnan, P. (2019). Environmental law casebook (4th ed.). LexisNexis.

- National Green Tribunal. (2024, March). Order on Kamakhya Corridor Project environmental petition (Application No. [Insert Number]). Principal Bench, New Delhi.

- Singh, S. (2021). Sacred geography and environmental law: The confluence of culture and conservation. Indian Law Review, 5(3), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/24730580.2021.1895510

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2003). Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000132540

- Upadhyay, S. (2022). Environmental jurisprudence in India: A practitioner’s perspective. Eastern Book Company.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press.