We are in the middle of a climate crisis, and it has already impacted communities worldwide. In India, where a significant portion of the population relies on agriculture and natural resources for their livelihoods, the effects of climate change are particularly pronounced. The challenges are stark: erratic monsoons, severe droughts, and scorching heatwaves are not just abstract issues; they are real threats now that jeopardize food security, economic stability, and lives of many.

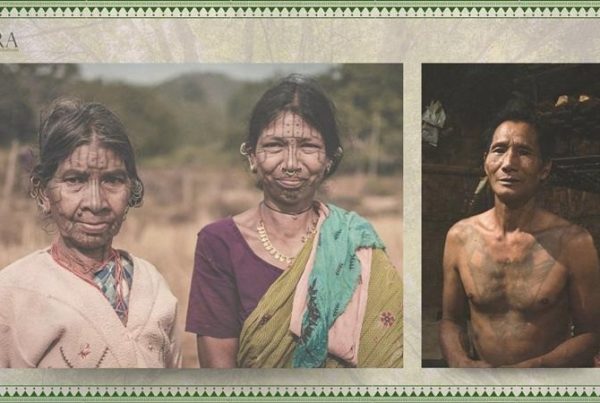

As we scramble for solutions, smallholder farmers and indigenous people across the world have stepped up as crucial actors in the fight against climate change. These grassroots guardians hold the key to mitigating and adapting to environmental changes, all while advancing sustainable development in ways we haven’t even fully recognised.

Indigenous people and local communities are custodians of approximately one-third of the world’s forests and 80% of the world’s biodiversity. They also manage at least 24% of the total carbon stored above ground in world’s tropical forests. These aren’t just mere statistics, but a testament to the indispensable role these communities play in environmental conservation. Their traditional knowledge, passed down through generations encompassing sustainable agricultural, water management, and restoration and conservation, is tailored to the local environment and needs. They often specialise in indigenous occupations within their territories, which are inherently sustainable and harmonious with nature. By tapping into this wealth of wisdom, these communities are finding innovative solutions to climate-related challenges. However, traditional knowledge is slowly either being lost across the world or has come under immense climate and anthropogenic pressures, making centuries old sustainable practices, unsustainable.

For instance, the use of fire by indigenous communities for centuries has shaped landscapes in ways that increased the land’s resilience. In Australia, communities have practiced fire-stick farming, also known as cultural burning for thousands of years, much before modern forest departments across the world started using it. Communities ignite small, controlled fires to clear underbrush, encourage the growth of specific plant species, and create mosaics of different vegetation stages. This practice reduces fuel loads, mitigating the risk of large, uncontrolled wildfires, and promotes biodiversity by creating a variety of habitats for different species. A technique that is deeply rooted in Aboriginal culture and spirituality, with knowledge passed down through generations, it is tailored to local ecosystems, taking into account seasonal weather patterns, vegetation types, and animal behaviours. Fire-stick farming not only maintains ecological balance but also supports the cultural and social structures of Aboriginal communities.

Over the last ten years, fire-prevention programs on Aboriginal lands in northern Australia have successfully reduced destructive wildfires by 50%. These efforts, which incorporate ancient fire management techniques, have also achieved a modern advantage – communities implementing these controlled burns have earned $80 million through Australia’s cap-and-trade system due to the significant reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from wildfires in the region – by about 40%.

Similarly, communities in northeast India have practiced jhum – slash and burn – cultivation for centuries. This practice involves slashing of woody vegetation, burning, and clearings including debris followed by the cultivation of crops in which upland paddy was the predominant crop. One of the strengths of practicing jhum cultivation lies in its ability to sustain a diverse range of plants – Rice, Millet, Pulses, and vegetables thrive in these fields, which contribute to the food security and livelihood of the community. It used to be a 15- 20 year cycle of cultivation in one area which gradually helped to revive the soil. However, over the past decades it has become unsustainable due to cycle going from 15-20 to 2-3 years. This has consequences for soil health as it would not have enough time to revive its natural properties leading to a massive decline in soil fertility. There is a need to support these communities to reduce reliance on jhum, and return them to the sustainable form of the traditional practice.

While the practice of jhum is a significant challenge in northeast India and needs urgent attention, the Chakhesang tribe in the Phek district of Nagaland, practices a unique integrated farming system – Zabo – from which we can take many lessons. The word “Zabo” means “impounding of water” and reflects the system’s emphasis on water conservation, using an intricate blend of agriculture, forestry, and water management. This indigenous technique involves creating terraced fields on hill slopes, which are meticulously designed to capture and store rainwater. This water is then used for multiple purposes, including irrigation, fish farming, and domestic uses. The Zabo system integrates crop cultivation with animal husbandry and forestry – farmers plant a diverse array of crops in the terraced fields, ensuring soil health through crop rotation, and the livestock providing manure that enriches the soil. Forested areas are maintained around the terraces to prevent soil erosion and enhance water retention. This sustainable approach not only secures food and water resources for the community but also preserves the ecological integrity of the region.

Traditional knowledge and indigenous practices such as these offer valuable insights for addressing modern environmental problems. Here we’ve talked of just two practices and the role they can and already are playing in the fight against climate change. There are countless other examples from indigenous communities across the world that can help us develop solutions for diverse climate and natural resource related challenges. These practices are inherently sustainable, having evolved over centuries in harmony with local ecosystems. They emphasize biodiversity, resource conservation, and resilience, which are crucial for combating contemporary issues like climate change, habitat destruction, and resource depletion.

Integrating scientific technology with these traditional practices can amplify their effectiveness and scalability. For instance, satellite imagery and geographic information systems (GIS) can enhance the precision and planning of controlled burns in fire-stick farming, ensuring they are conducted safely and effectively. Similarly, modern hydrological models can optimize water management in systems like Zabo, improving water conservation and distribution. Moreover, scientific research can validate and refine traditional methods, making them more acceptable to policymakers and broader communities, helping with their scalability. This integration facilitates a holistic approach to environmental management, combining the wisdom of indigenous practices with the advancements of modern science. It can lead to innovative solutions that are not only effective but also culturally respectful and inclusive.

Recognizing the importance of indigenous knowledge systems, initiatives need to be aligned in order to empower local communities and indigenous people in climate action. Collaborative projects between governmental agencies, NGOs, and indigenous communities are facilitating the documentation and preservation of traditional knowledge while integrating it into mainstream climate policies and programs. Ensuring participation and representation of indigenous peoples in decision-making processes related to natural resource management and climate adaptation is crucial and by respecting their rights and autonomy, these initiatives will not only foster environmental sustainability but also help promote social justice and cultural preservation.

Several countries, including India, have pledged to support community rights to manage forests and lands in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. This recognition underscores the significance of local-level action in combating climate change. Therefore, protecting the livelihood systems of indigenous people is not only essential for preserving cultural heritage but also for improving food security and environmental conservation. Their traditional knowledge, resilience, and community-driven approaches offer valuable insights and solutions in the face of growing environmental challenges. By empowering these grassroots actors and amplifying their voices, a path towards a more sustainable and equitable future can be forged for all. As we navigate the complexities of climate change together as the inhabitants of this planet, let us recognize and celebrate the invaluable contributions of those on the frontlines of environmental stewardship.

- FAO (2018): https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en?details=CA0829EN

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/08/09/empowering-indigenous-peoples-to-protect-forests

- https://www.fao.org/redd/areas-of-work/stakeholder-engagement/en/

- https://landcareaustralia.org.au/project/traditional-aboriginal-burning-modern-day-land-management/

- https://www.sbs.com.au/voices/article/firestick-farming-how-traditional-indigenous-burning-protected-the-bush/xc9ovv8l7

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/16/world/australia/aboriginal-fire-management.html

- https://eciph.in/opinions/jhum-cultivation-in-manipur-hills-district-nurturing-tradition-navigating-challenges/

- Singh, R. K., Singh, V., Rajkhowa, C., & Deka, B. C. (2012). Zabo: A Traditional Way of Integrated Farming. BC Deka, MK Patra, A. Thirugnanavel, D. Chatterjee, Borah, Tasvina R. & SV Ngachan (Eds), Resilient Shifting Cultivation: Challenges and Opportunities, 114-117.

- GCF. 2018. Indigenous Peoples Policy. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/ip-policy.pdf