As the biodiversity crisis intensifies, the 16th Conference of the Parties (COP16) to the Convention on Biological Diversity, held in Cali, Colombia, must serve as a turning point for global action. It is an opportunity to reflect on our current actions and prioritise global commitments to protect our natural world and ensure that the benefits of biodiversity are preserved for future generations.

Building on the Kunming-Montreal Framework

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) adopted at COP15 in 2022, sets the vision for 2050, guiding efforts towards living in harmony with nature. The GBF comes with 23 action-oriented targets and four overarching goals for 2050 and with 2030 as the milestone for many GBF goals, including placing 30 percent of land and sea areas under protection and 30 percent of degraded ecosystems under restoration by 2030, reducing pollution, and phasing out agricultural and other subsidies harmful to nature. The key challenge and a major discussion around COP16 have been that it is essential that these targets don’t face a fate similar to the Aichi.

Unlike the legally binding Paris Agreement, the GBF relies on voluntary commitments, raising concerns about accountability and progress tracking. The ambitious commitments made two years ago at COP15 look like a distant reality, especially as the gap between promises and actions widens. This makes it essential for COP16 to deliver real results. While the awareness factor on biodiversity has improved, reflected in the doubled participation this year, the meeting lacked a concrete decision and agreement on the financial front[1].

Progress so far after COP16

The spotlight for this year was on monitoring and accountability mechanisms, where indicators for many targets, incomplete or missing, were planned to be finalised. These indicators are essential for measuring success and ensuring transparency. The GBF emphasised on resource mobilization and capacity building, leveraging various funding models—such as blended finance, conservation trust funds, debt-for-nature swaps, and innovative tools like biodiversity credits and certificates—to bridge funding gaps. But there was no agreement on a roadmap to ramp up funding for biodiversity protection.

While there was progress on digital sequence information (DSI) benefit-sharing and biodiversity mainstreaming across sectors, there were significant setbacks regarding delays in biodiversity funding agreements. The lack of consensus on creating a new fund for developing countries and meagre pledges to the existing Global Biodiversity Framework Fund raised concerns about the commitment to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

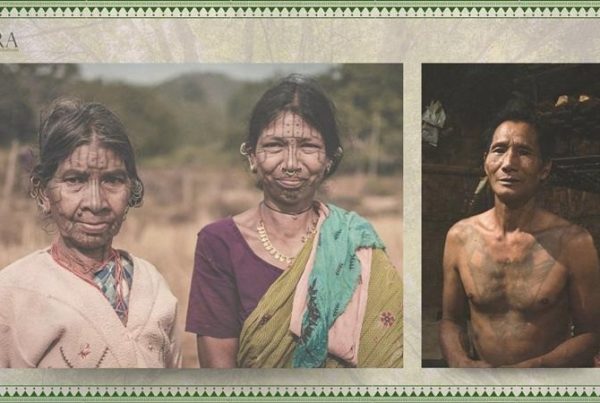

Positive developments included the increased participation of Indigenous and local communities, as well as new biodiversity and health action plans. Their involvement is critical, as they hold the key to sustainable practices that can benefit both biodiversity and local economies.

Key takeaways included a call to unify biodiversity and climate actions, growing corporate alignment with the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), a push for tech-driven nature metrics, and concerns about insufficient biodiversity funding. Despite ongoing discussions since COP15 about increasing biodiversity funding, no concrete decisions emerged from this meeting.

What was Promised vs. What was Delivered

Looking back at GBF, it was envisioned as a turning point in how we protect our planet’s biodiversity, however, the latest Global Biodiversity Outlook reveals concerning trends. Only 15%of the signatory nations submitted their National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) before the COP 16 as per the timeline, while India is among the countries that are yet to submit the NBSAPs.

According to the estimates, there is a financial gap of around $700 billion annually for biodiversity restoration and protection. To address this, we need to mobilise at least $200 billion per year from public and private sources, phase out or reform subsidies that harm biodiversity by at least $500 billion annually, and raise international financial flows from developed to developing countries to at least US$ 30 billion per year.

However, national commitments are falling short, yet again. Only $15.4 billion was raised in 2022against a $30 billion annual goal set for 2025. Additionally, inadequate monitoring and reporting systems hinder progress tracking and accountability[2].

The 30×30 Goal Reality

Currently only 17% of land and 8.3% of marine areasare protected globally, far below the target to protecting 30% by 2030. Even more concerning,only 30-45% of these protected areas are effectively managed, according to assessments by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The 30×30 initiative is not just about designating protected areas; it’s about ensuring those areas are truly safeguarded against human activities that threaten them. Recent studies show that 32.8% of protected areas are under intense human pressure, while only 1.44% of high seas are managed within marine protected areas. Moreover, Indigenous territories which cover about 32% of the world’s remaining wilderness, receive disproportionately less global conservation funding, highlighting a critical flaw in our conservation strategy. We must focus on both the quantity and quality of protection[3].

Financial Conundrum

Despite these successes in biodiversity conservation, the financial landscape remains troubling. Harmful subsidies totalling about $1.8 trillion annually continue to drive biodiversity loss, while only about 8% of climate finance addresses biodiversity co-benefits. The estimated annual biodiversity financing gap of $700 billion represents just 0.7% of global GDP, emphasizing the need for innovative solutions3.

Emerging strategies like biodiversity-linked bonds, which have seen a growth of 127% since 2022, and use of Nature-based carbon credits, projected to reach around $50 billion by 2030 are promising. Sovereign debt-for-nature swaps have also seen successes in countries like Ecuador and Gabon[4]

Inspiring examples, such as Costa Rica’s Payments for Environmental Services (PES) program has made remarkable strides in reversing deforestation by compensating landowners for conserving forests instead of cutting them down. Between 1997 and 2004, Costa Rica invested around $200 million in PES, protecting over 460,000 hectares of forests while providing income to more than 8,000 forest owners[5].

Namibia’s communal conservancy program has similarly empowered local communities to manage wildlife sustainably, leading to a 150% increase in participating areas.[6]

Recent analysis from Newman & Cragg (2020) shows that natural products and their derivatives contributed to approximately 25.1% of all FDA-approved drugs, with many of these discoveries stemming from traditional knowledge[7]. However, Indigenous communities who hold this valuable traditional knowledge often receive inadequate compensation through existing benefit-sharing arrangements under the Nagoya Protocol framework (UNEP CBD, 2023)[8].

The proposed Digital Sequence Information (DSI) framework aims to rectify this by establishing benefit-sharing agreements and creating a Global Biodiversity Fund to support conservation in Indigenous territories. At COP 16, the ‘Cali Fund’ was established to ensure that 50% of profits from companies using DSI benefit Indigenous and local communities, particularly women and youth[9].

India’s Stance

India’s leadership in biodiversity initiatives shows both promise and complexity. With a network of 1014 Protected Areas, India has achieved an impressive 27% protected area coverage, surpassing its initial goals ahead of schedule. Additionally, the country has implemented the world’s first national biodiversity finance plan through its Green Credits Program, aimed at ecosystem restoration.

However, significant challenges still persist. Approximately 45% of tiger corridors face severe fragmentation due to infrastructure development[10], while Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) account for only 5% of India’s total Protected Area network, representing less than 0.3% of the country’s total land area. Although, some MPAs are effectively protected from threats like overfishing and pollution[11], the ongoing conflict between development projects and the need for biodiversity protection remains pertinent.

While India’s commitment aligns with global targets, it still requires consistent action and transparency moving forward.

What Can be the Way Forward Beyond the Talks

Our vision for the future is one where biodiversity is valued and protected, not just in words but in deeds. Weak enforcement in protected areas and the lack of integration of biodiversity goals into national economic plans hinder our progress in achieving those targets. The NBSAPs need not only set ambitious goals but also outline well-defined action plans and strategic approaches to achieve them. While the GBF may not be legally binding, partner countries can increase the likelihood of success by aligning their policies with GBF goals and integrating these into national legislation to avoid repeating of the Aichi shortcomings.

Successful integrated strategiesinclude mangrove restoration projects, which offer coastal protection and carbon sequestration benefits, and agroforestry systems that enhance biodiversity and climate resilience through sustainable land-use practices. Additionally, developing urban green corridors can improve wildlife connectivity while mitigating urban heat islands, demonstrating the multifaceted benefits of merging ecological health with climate action.

The intricate connections between climate change and biodiversity loss cannot be overstated: one cannot be tackled without the other. Research indicates that nearly 40% of species could face extinction due to climate change by 2050, while nature-based solutions could provide up to 37%of climate mitigation needed by 2030.

It is imperative that we recognise biodiversity protection and climate change reversal as two sides of the same coin, fostering a unified approach to safeguarding our planet for generations to come.

[2] COP16 Highlights Urgent Need for Biodiversity Finance, Progress on Target 19a Assessed

[3] International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (2022). Global Biodiversity Outlook 5

[4] Biodiversity Bonds – Climate Capital – Pictet Asset Management

[6] Conserving Wildlife and Enabling Communities in Namibia – WWF

[8] UNEP CBD (2023). “Assessment Report on the Implementation of the Nagoya Protocol”