The Himalayas, often referred to as the “Third Pole,” hold the largest reserve of ice and snow outside the polar regions, sustaining rivers like the Ganges, Indus and Brahmaputra, lifelines for over 1.3 billion people. But this lifeline is melting — and fast.

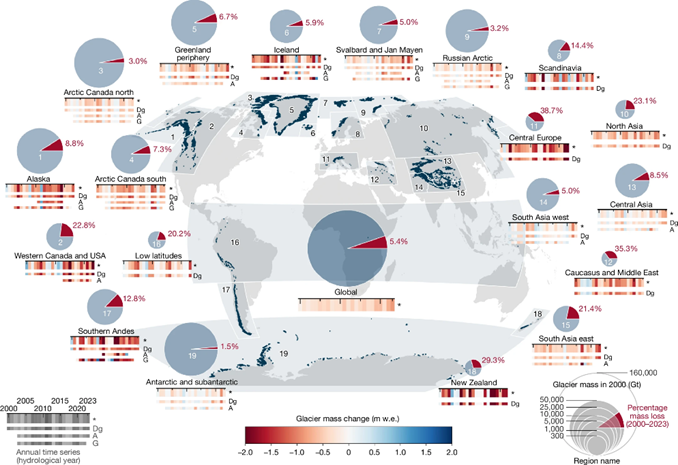

Between 2000 and 2023, Earth’s glaciers lost 6.5 trillion tonnes of ice, contributing to an 18mm rise in global sea levels. On average, 273 billion tonnes of ice melt annually which is enough to sustain the world’s water consumption for 30 years.

Himalayan glaciers are among the fastest melting, disrupting drinking water sources, agriculture, and energy production, in India and beyond. Scientists warn that if global emissions continue unchecked, the Himalayas could lose up to two-thirds of their glaciers by the end of the century.

Figure 1: Community estimate of global glacier mass changes from 2000 to 2023, (Source: Nature)

Himalayan Glaciers: Sustaining Life and Land

Himalayan glaciers act as natural water towers, storing and gradually releasing freshwater to sustain major river systems that support food production for about 38 million people and provide livelihoods for nearly 129 million farmers (Biemans et al., 2019). They also regulate climate patterns, reflecting sunlight to balance the Earth’s energy, and driving the Southwest Monsoon.

Beyond their ecological role, glaciers like Gangotri and Yamunotri hold deep cultural and spiritual significance, revered as sacred sources of life-giving rivers. For centuries, local communities have carried out annual pilgrimages, prayers, and rituals to honour the rivers’ origins.

These glaciers – and many more – are in rapid decline, putting ecosystems, economies, and traditions at risk. Several interconnected factors are accelerating this crisis – rising temperatures, increasing global emissions and unchecked human activities – are resulting in the melting glaciers faster than they can be replenished. Black carbon pollution – soot from vehicles, industries, and biomass burning is particularly harmful to them as it settles on the ice, darkening its surface and accelerating melting.

The Consequences: A Domino Effect

The rapid fallout of this threatens India’s water security, energy production, and food systems – reduced meltwater disrupts hydropower generation and irrigation, especially in the Indo-Gangetic plains, leading to crop failures and endangering livelihoods.

As glaciers shrink, biodiversity suffers too and alpine flora and fauna are struggling to adapt to rising temperatures, leading to species loss and ecological imbalances. Meanwhile, glacier-dependent tourism, from trekking to pilgrimages, are facing economic decline. The geopolitical implications are also high as major Himalayan rivers have cross border flow, and reduction in water availability could escalate regional conflicts over water-sharing agreements.

Glacial Lake Outburst Floods: An Alarming Consequence

As glaciers retreat, meltwater accumulates leave behind unstable natural ice or moraine dams, forming glacial lakes. This growing network of unstable lakes heightens the risk of sudden breaches, leading to Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs). These powerful floods unleash massive volumes of water, debris, and rocks downstream, impacting communities, infrastructure, and agricultural lands.

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) reports that climate-induced glacial retreat across the Hindu Kush Himalaya has led to the formation of numerous new glacial lakes, which are the major cause of GLOFs. In Arunachal Pradesh alone, between 1988 and 2020, a staggering 110 glaciers vanished, reducing the total glacier count from 756 to 646. This led to a 47% shrinkage in glacial area, exposing more bedrock and increasing GLOF risks.

The risks extend far beyond immediate flooding. Receding glaciers weaken natural water storage systems, endangering millions who depend on these seasonal flows. The increased frequency of such events highlights the urgent need for strengthening disaster preparedness and enhancing early warning systems. Implementing glacial lake monitoring programs, using satellite data and remote sensing technologies, can help track lake expansion and assess structural vulnerabilities.

The 2021 Chamoli Flash Flood in Uttarakhand: What can we learn from it?

On February 7, 2021, a devastating flash flood struck Uttarakhand’s Rishi Ganga Basin, claiming 80 lives, and leaving 124 people missing. It damaged critical infrastructure, including the Rishi Ganga and Tapovan Vishnugad Hydropower Projects. Initially thought to be a GLOF, later studies confirmed the disaster stemmed from a massive ice-rock avalanche from a hanging glacier near Ronti Peak. Roughly 22 million cubic meters of ice and debris crashed into the valley, triggering powerful debris flow that was intensified by rising temperatures and rapid warming after heavy snowfall, further intensified by the region’s steep terrain.

The flood resulted in displacement, economic losses, and environmental risks from sediment deposition downstream. It also stressed the urgency for enhanced glacier monitoring through satellite imaging, increasing community awareness, and improving emergency response training can significantly reduce future risks.

The 2023 Sikkim Glacial Lake Outburst Flood: Were we better prepared?

On October 3, 2023, South Lhonak Lake, a GLOF in Sikkim unleashed around 50 million cubic meters of water – equivalent to 20,000 Olympic-sized pools – after 14.7 million cubic meters of frozen moraine collapsed. The resulting 20-meter-high wave devastated communities along the Teesta River, impacting Sikkim, West Bengal, and Bangladesh.

The floodwaters also carried an estimated 270 million cubic meters of sediment, damaging hydropower stations, farmland, and settlements along its path. Mitigation efforts like siphons (installed in 2016) and an automated weather station (added in September 2023) reduced the impact of the disaster, however it did expose gaps in risk assessments, particularly regarding sediment transport. This event highlights the urgent need for stronger Early Warning Systems (EWS), resilient infrastructure, and better transboundary coordination among Himalayan nations.

Pathways to Resilience: Science, Technology and Community Action

Addressing the risks of glacier melting and GLOFs demands a multi-faceted approach that blends scientific research, technological innovations, and community-driven conservation efforts. Hydrological simulations and Artificial Intelligence-driven predictive models, like those developed by the National Institute of Hydrology (NIH) in Roorkee, simulate GLOF scenarios triggered by rainfall or seismic activity, refining evacuation plans and strengthening infrastructure resilience. Early warning systems are equally vital – Bhutan’s successful real-time sensor networks around high-risk lakes offer a proven example India can replicate, supported by satellite data, to provide timely alerts and empower vulnerable Himalayan communities.

Community-led initiatives further bolster resilience. The Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) developed the Ice Stupas Project in Ladakh demonstrate how artificial glaciers can store winter meltwater for use during dry months, reducing reliance on natural glaciers. Reforestation efforts in Himachal Pradesh stabilize soil, prevent excessive runoff, and sustain glacier-fed streams. Training local youth through programs like the Glacier and Climate Change Initiative (GCCI) fosters a decentralized network of observers, strengthening grassroots monitoring and early response.

Building flood-resistant housing, embankments, and reinforced bridges can also help mitigate the impact of GLOFs. Regular evacuation drills and awareness campaigns in high-risk regions like Sikkim and Uttarakhand ensure that communities know how to respond to these emergencies.

Way Forward

GLOFs are no longer rare disasters – they’re a ticking clock. Mitigating them demands more than technology and research. It requires collective action from governments, scientists, and communities alike. By merging modern innovations with traditional knowledge and Nature-based Solutions, we can safeguard these fragile mountain landscapes and the millions who rely on them.

The glaciers won’t wait – and neither should we.

References

- Understanding the flash flood event of 7th February 2021 in Rishi Ganga basin, Central Himalaya using remote sensing technique – ScienceDirect

- https://www.nextias.com/ca/editorial-analysis/12-12-2023/threats-from-contracting-glaciers

- Major Glaciers in India: Location & Significance

- The Himalayan Glaciers Are Melting—What That Means for India’s Future – discoverwildscience

- https://www.ndma.gov.in/sites/default/files/PDF/Guidelines/Summary-for-Policy-Makers-on-Guidelines-on-Management-of-GLOFs.pdf

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08545-z#Fig1

- https://www.ias.ac.in/article/fulltext/jess/134/0027

- Understanding the flash flood event of 7th February 2021 in Rishi Ganga basin, Central Himalaya using remote sensing technique – ScienceDirect

- https://www.antarcticglaciers.org/wp-content/plugins/antarcticglaciers-pdf/download.php?p=8882

- Co-production processes underpinning the ecosystem services of glaciers and adaptive management in the era of climate change – ScienceDirect

- Importance of snow and glacier meltwater for agriculture on the Indo-Gangetic Plain | Nature Sustainability

- Mountain Biodiversity, Its Causes and Function

- Elevating Mountains in the Post-2020: Global Biodiversity Framework 2.0 | GRID-Arendal

- Sixth Assessment Report — IPCC

- World heritage glaciers: sentinels of climate change – UNESCO Digital Library

- The Sikkim flood of October 2023: Drivers, causes and impacts of a multihazard cascade | Science