Tattooing, as a cultural phenomenon, precedes written language in many parts of the world and has consistently served as an embodied archive of human expression. As both ritual and art form, it intersects with healing, identity, cosmology, and social regulation. From the carbon-ink lines on Ötzi the Iceman, Europe’s oldest natural mummy, to the iconographies of Polynesian tā moko and Japanese irezumi, tattooing has operated as socio-spiritual codification and corporeal inscription[1],[2],[3]. The Pazyryk mummies of the Altai Mountains, with stylized tattoos of deer, monsters, and griffins, exemplify how body inscriptions functioned as cosmograms – visual worldviews anchored in the human–nonhuman continuum.

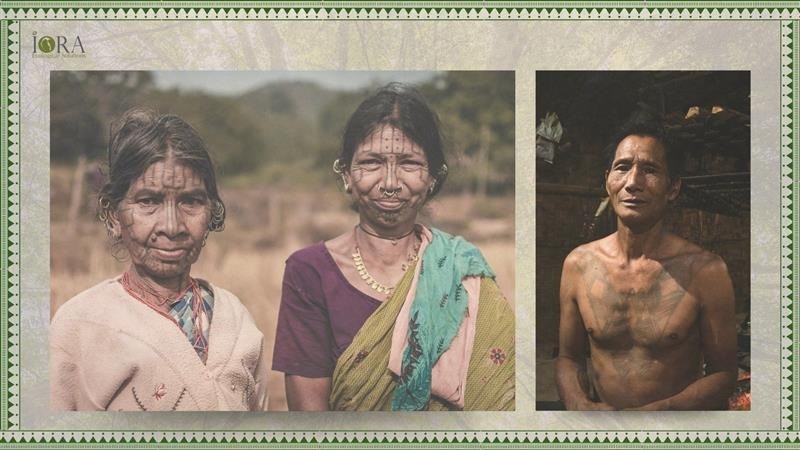

In the Indian subcontinent, the persistence of tattooing across tribal cultures reinforces its centrality in the intangible cultural services landscape[4],5. Unlike modern practices focused on aesthetics, indigenous tattooing, particularly among the Baiga, Apatani, Bhil, and Rabari communities, and several others, is rooted in a shared socio-ecological imaginary[5]. These tattoos are not decorative but act as mnemonic devices, ritual markings, and socio-religious scripts. Krutak[6] describes traditional tattooing as a “visual language”, transmitted intergenerationally through oral practices with meanings persisting in the collective community memory. Tattooing then is more than body modification; it is a ritual aesthetic linking personhood to ecology, beliefs, and kinship, thus forming a crucial reservoir of Indigenous Local Knowledge systems.

Despite their depth and symbolism, tattoos remain absent from most frameworks valuing cultural ecosystem services (CES). Defined in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment[7], CES include spiritual, aesthetic, and cultural benefits from nature. Traditional tattooing practices with their ecological knowledge, ritual significance, and enduring commitment represented an overlooked CES dimension. Recognizing them would affirm embodied human-nature relationships and eco-cultural identities vital to sustainability.

Tattooing and Nature among Indian Tribal Communities

In tribal India, the act of tattooing, often called Godna, is deeply entwined with ecological awareness, spiritual safeguards, and indigenous belief systems. Among the Baigas of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, it reflects an animistic worldview. Their nature-inspired motifs, mountains, fish, bee-hives, grains, suns, cow-eyes, moon shapes, and geometric lines, represent ecological elements central to their lifeworld[8],[9]. Baiga tattoos are inscribed over the life course, each denoting rites of passage from marriage, childbirth, or initiation into womanhood[10], thereby encoding biographical and social narratives. The use of indigenous materials such as ramtila oil, sal gum, and soot further anchors the practice to the local ecological economy[11]. Similar practices exist among the Apatani of Arunachal Pradesh[12] where soot mixed with animal fat and inserted with thorns created facial tattoos that served as protection. Apatani women were tattooed from forehead to chin to deter inter-tribal abductions, illustrating how tattooing can simultaneously be a technology of resistance and survival. Among Bhil women, bird and scorpion motifs near the eyes serve as talismans against the nazar (evil eye) and as assertions of beauty[13]. Rabaris, semi-nomadic pastoralists in Gujarat, tattoo camels and dotted lines to differentiate sub-groups and symbolize mobility and trade[14].

These practices open new terrain for communication studies[15]. Tattooing functions not only as a ritual but also eco-conversational communication. Each tattoo becomes a statement of environmental consciousness. Scholars argue that care for nature is often communicated through symbols that fuse human and nonhuman worlds, thus serving as enduring gestures of care and markers of eco-cultural identities.

The Cultural Devaluation of Tribal Tattooing

Despite their significance, tribal tattoo traditions in India have long faced marginalization and erasure. Colonial and postcolonial regimes recoded them as primitive, unsanitary, or backward. Caste ideologies further stigmatized tattooed women, who reported ridicule, discrimination, and exclusion from institutional spaces[16]. The paradox is stark: urban India embraces it as individual freedom and aesthetic experimentation, while tribal tattoos are seen as illiteracy and cultural stagnation. This asymmetry reveals deep injustice in how indigenous practices are perceived.

The loss of tattooing is not merely symbolic – it is an epistemological rupture. As forest communities face displacement, their traditional ecological knowledge systems are eroded. While there is no formal ban on tattoos, historical assimilation and social regulations discouraged tattoos11, leading younger Baigas in places like the Achanakmar–Amarkantak Biosphere Reserve to prefer modern aesthetics for social mobility[17].

Generational Discontinuities in the Transmission of Traditional Tattooing Knowledge

The intergenerational transmission of tattooing knowledge among tribal communities is mediated through women, often matrilineal artisans who inherit designs, tools, and techniques from their mothers and grandmothers. These women, known as Badnins in Baiga communities, do not work from templates or sketches[18]. The designs exist in memory and are drawn freehand, inscribed through pain and patience. Yet, this lineage of artisanship faces increasing precarity. The socio-economic vulnerability induced by deforestation, resettlement, and economic stagnancy, has accelerated this erosion. Younger women, exposed to urban education and media, often experience shame or ambivalence about their inked bodies, opting for minimal or no tattoos. In some areas, traditional designs have given way to hybrid motifs influenced by neighboring tribal groups, diluting both the semiotic clarity and the integrity of the original markings.

This generational disconnect reflects a structural failure to recognize and support the intangible cultural heritages of India5. While governmental and non-governmental initiatives exist to promote tribal handicrafts and visual arts, body-based practices remain under-researched, under-funded, and under-valued.

Re-inscribing Tattooing in India’s Conservation Imagery

The marginalization of indigenous tattooing is not inevitable, rather stems from policy orientations, epistemological bias, and socio-cultural stigmas. Reinscribing tattooing within India’s broader conservation fabric requires a multi-scalar intervention: ethnographic documentation, policy recognition, community-led revival, and public sensitization.

Globally, seafaring communities have long used tattoos as records of their maritime journeys, spiritual beliefs, and ecological awareness. From North Star motifs to sea turtles symbolizing longevity, these markings bridged ecological knowledge with cultural memory. Today, marine conservationists are revisiting these tattoos to revive ancestral knowledge. In Hawaii, Polynesia, and New Zealand, collaborations between tattoo artists and marine biologists have revealed forgotten spawning sites, migratory routes, and traditional navigation patterns, now used to inform marine protected area design and species management[19]. There is also growing momentum among cultural preservationists, anthropologists, and tribal activists to revalorize tattooing as a critical component of India’s intangible cultural heritage. For instance, Baiga women are reclaiming Godna as a badge of identity and pride, while NGOs are working with Badnins to archive designs and explore eco-friendly ink alternatives that preserve traditional methods. Contemporary artists are beginning to collaborate with tribal communities to ethically adapt motifs for new media, fashion, and public art.

Crucially, such revival efforts must resist commodification. The goal is not to aestheticize indigenous tattoos for metropolitan consumption, but to safeguard their ontological meanings, ecological inscriptions, and ritual logics. As India navigates its plural modernities, the recognition of tribal tattooing as both an aesthetic and epistemic tradition is imperative. Tattoos are not mere ink – they are scripts of survival, cartographies of ecological wisdom, and acts of resistance. To overlook them is to erase a profound modality of cultural expression and ecological consciousness.

In the words of one elder Baiga woman: “We do not wear tattoos to look beautiful. We wear them so the forest remembers us when we are gone.”

[1] Gilbert , S. 2000 . Tattoo history: A source book. With the collaboration of C. Gilbert New York : Juno Books

[2] Rudenko, S. I. 1970 [1953]. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron-Age Horsemen (trans. M. W. Thompson). Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

[3] Frechette, M. (2024). Embodied Environmentalism: The Socioecological Politics of Tattoos, Storytelling, and the Body (Master’s thesis, University of Toronto (Canada)).

[4] Martí, J. (2010). Tattoo, cultural heritage, and globalization. Scientific Journal of Humanistic Studies, 2(3), 1-9.

[5] Ghosh, P. (2020). Tattoo: A Cultural Heritage. Antrocom: Online Journal of Anthropology, 16(1).

[6] Krutak, L. (2015). The cultural heritage of tattooing: a brief history. Tattooed skin and health, 1-5.

[7] https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.319.aspx.pdf

[8] https://www.sahapedia.org/traditions-skin-baiga-women-and-their-tattoos.

[10] Goswami, M. P. (2015). Tattoo: A Cultural Expression of the Baiga Women. Journal of Tribal, Folk and Subaltern Studies

[11] Bandhu, M. S., Singh, M. N. K., & Sharma, V. N. (2024). A Study of the Baiga Women’s Tradition of Tattoos, Modernization of this Art, and Situation of Tattoo Industry in India.

[12] Kale, S. (2021). A look at India’s tribes and its traditions of tattoos. Homegrown. https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-voices/a-look-at-indias-tribes-and-its-traditions-of-tattoos

[13] https://www.savaari.com/blog/history-and-symbolism-of-tribal-tattoo-india/

[14] Krutak, L. (2022). INDIA: LAND OF ETERNAL INK | LARS KRUTAK. Lars Krutak | Tattoo Anthropologist. https://larskrutak.com/india-land-of-eternal-ink/

[15] Weder, F., Burdon, J., & Kearney, C. (2023). Eco-cultural identity building through tattoos: a conversational approach. Frontiers in Communication, 8, 1197843.

[16] Kumar, A., & Thakur, A. (2022). The Study of Social and Cultural Values of Baiga Tribes in Madhya Pradesh. Archives of Psychiatry and Mental Health

[17] Baghel, Y. A., & Patil, G. (2022). Achanakmar-Amarkantak Biosphere Reserve: Development and traditional knowledge of Baiga.

[18] https://singinawajunglelodge.wordpress.com/2020/06/01/indigenous-tattoo-art-gets-a-new-inning/